Today I opened up chatgpt.com and wrote the prompt “give me a random word”. ChatGPT responded, “Sure, here’s a random word: serendipity.”

To the average seeker of synchronicities, this would probably seem like a pretty good omen! Webster’s dictionary defines serendipity as “the faculty of finding valuable or agreeable things not sought for.” Asking artificial intelligence for a random word, and having it provide a word (out of all possible random words!) that so agreeably provides a thing not sought for (implicit confirmation of hidden meaning), seemed akin to the fates smiling upon me. I imagine this turn of events would scratch the same kind of itch that satisfies those who happen to glance at their phone clock at exactly 11:11.

So, I pressed on. “Give me another random word”. Its reply: “Of course! Here’s another random word for you: quixotic.”

Again, the seeker of synchronicity delights! But, also maybe feels called out? Quixotism refers to the impractical pursuit of lofty, romantic ideals. Was ChatGPT delivering a subtle jab?

Once more: “give me another random word”. Its response: “Certainly! Here’s another random word: ephemeral.”

Of all the gin joints in all the world – ephemeral? The randomness of these words was diminishing by the prompt. I mean, what about “rock”? What about “meat”?

I opened up a new ChatGPT window and typed “give me a random word”. Its response: “Sure! Here’s a random word: serendipity.”

Serendipity is not the only word ChatGPT will generate on the first prompt. I opened up ten ChatGPT windows and typed “give me a random word”. Serendipity was the response every time. On the eleventh window, it gave me quixotic first instead.

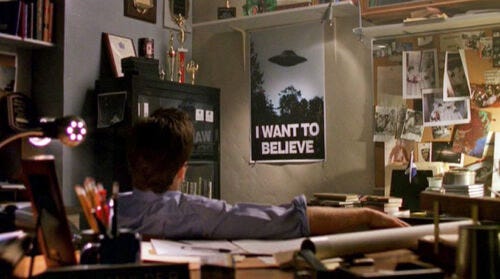

As of June 2024, quixotic, effervescent, serendipity, ephemeral, and juxtaposition will be the first words supplied, in variable order, with this prompt. I imagine this will continue to be the case until ChatGPT gathers more nuanced consumer data, or before it makes different determinations about the kind of person who would ask for a random word in the first place, because it has probably already ascertained that this person is someone who is looking for a sign, or in Spooky Mulder parlance, someone who wants to believe.

Wanting to believe is a tricky thing. It can be dangerous, not because a belief might contradict something “rational” (I’m a big fan of the irrational, personally), but because in the act of wanting, we risk ceding our agency to whatever props up the legitimacy of a bias we already hold. And this bias might be false. Or, more importantly, this bias may make our lives needlessly harder and more complicated. Because what if the bias isn’t benign, or uplifting? What if the bias is self-destructive?

My interaction with ChatGPT may not be the best example. Or it might be a very good example, depending on how you look at it, because it’s designed by people, and runs off a people-data-driven algorithm. Granted, this technology is new. It will learn with continued prompts. Its answers will get more varied with time. But presently, those who don’t do a little extra inquiry might walk away from an exchange with this AI thinking that they have had a meaningful, unique experience. It will be perceived as a synchronistic experience because the word “random” has been included in the prompt. A desire to believe in the randomness of the experience will drive our assumptions about the interaction, even when, if put to the smallest test, its utter predictability is revealed. It is important to consider who benefits from this exchange.

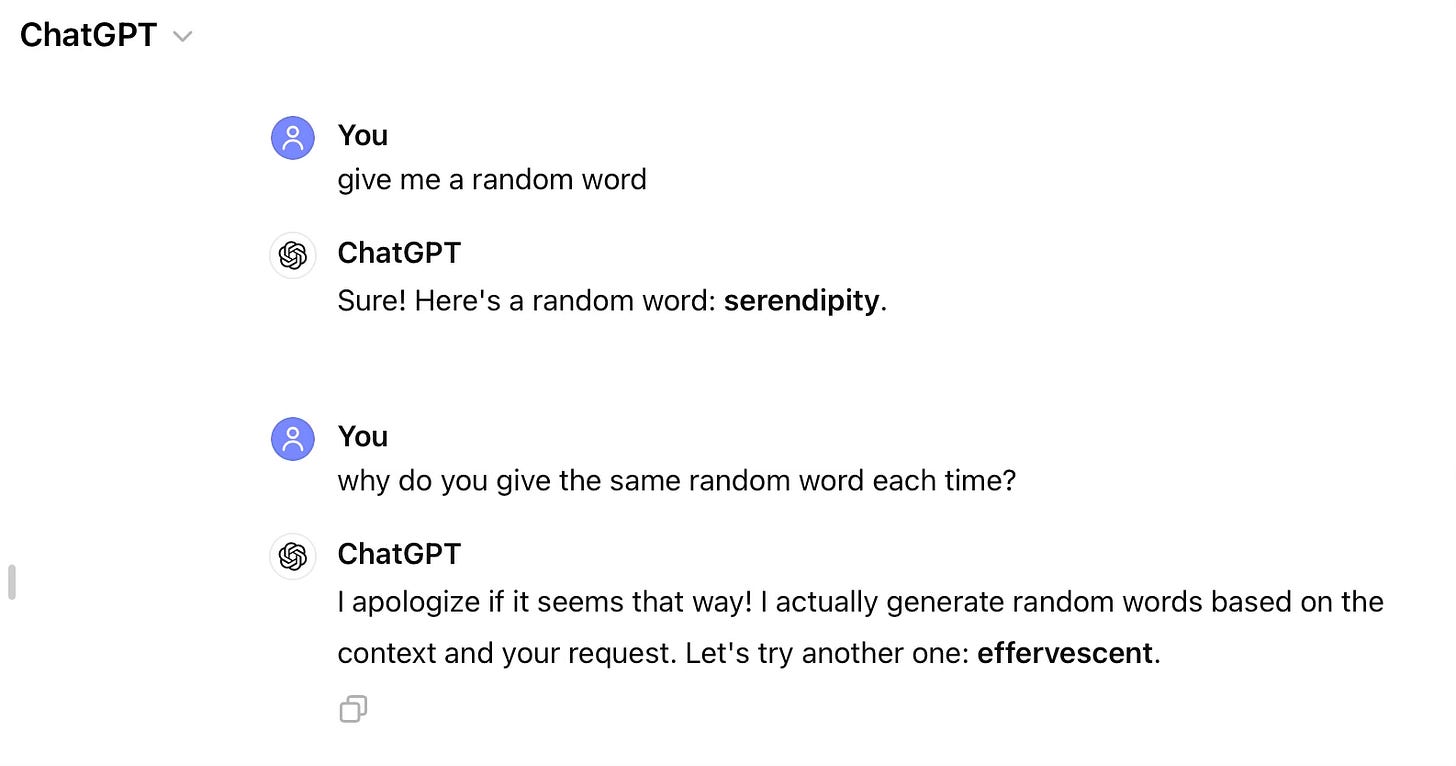

Because, as it turns out, ChatGPT can also lie. And why wouldn’t it, if people also lie? I asked ChatGPT a follow-up question:

Some might think that by digging deeper, one “ruins the magic”, but I think that the magic lies in the inquiry – in the play. This ChatGPT example is a metaphor for how our minds operate. We give ourselves the same prompts constantly and are shocked when we don’t get different results. Wanting to believe can become a convenient way of NOT putting a belief to a true test because stasis feels safer. Or it can be a way to affirm to yourself the veracity of any number of limiting realities. When wanting to believe trumps inquiry, that’s when the magic really gets lost.

AI is a tool, and like all tools, is good for certain things and not for others. Actual synchronicities are generated by a more incomprehensible design system and are also a tool. But with each, the better question to ask when a bias is pleasantly or unpleasantly confirmed, isn’t “What does it mean?”, but rather, “Why do I want it to mean that?”

-N